原文地址 摩天轮画廊

「此地彼时」

艺术家:史怡然,黄宝莹

策展人:顾灵

展览日期:2024/8/18—11/8

摩天轮画廊

Here and Then

ARTISTS:Shi Yiran, Huang Baoying

CURATOR: Gu Ling

DURATION:2024/8/18—11/8

Ferris Gallery

地方与时刻的关系总是百转千回。

尽管此次展出的作品中,黄宝莹画的几乎都是室内静物与居家场景,而史怡然的画则取自她旅行时暂住与探访的地点,但其实二人作画的动力都源于自身同异乡、迁徙的密切关系:从深圳到纽约,“家” 对长年留学旅居的宝莹来说一直都是临时的、不稳定的,频繁搬家的常态以及摇摆于主客身份认同的不安全感随着最近一次搬家转向了更为稳定与松弛的状态;从内蒙古到杭州,时间并没有磨淡史怡然客居异乡的无根感,反而在近年生发出对故乡的浓厚兴趣,尤其着迷于了解长时段的地方历史,她前往呼伦贝尔与大兴安岭的人文地理考察正是缘起于此。

二人的绘画都是写实、具象的,可并非为了还原现实,即便观者可以轻松认出画中的盆栽,插花,焰火,窗帘,还有台灯,玩偶,地图,博物馆陈列柜。它们在画中组织为对流淌于时光中的现象的观察:看似安静,实则暗流涌动。安德烈 · 塔可夫斯基在其电影创作笔记《雕刻时光》中写道:“静止于某一刻,但它同时浸润在连续的时间之流中,运载着丰沛的情感与思绪。…… 时间是一种状态,是一种火焰,在其中居住着人类心灵之火。…… 时间和记忆交融,有如一枚勋章的两面。” 因而,此时此刻几乎是不可得的,试图捕捉它的任何努力都只能定格于彼时;唯有通过距离与区隔,才能重访当时当刻。此次展出的作品,均为这种距离与区隔营造出空间,甚至更进一步,绘画本身成为一个地点。这些地点既可独立存在,亦可组合起来,成为在时光中旅行或驻留的生动注解。

二人过往的绘画就展现出时空的复数性,通过拼贴与重叠的方法将多来源的形象并置于同一画面。正如理查德 · 麦奎尔在其开创性的图像小说《这里》 把新泽西州的一幢房子穿越几百万年的时光流转以多窗格的形式并置于每页纸上,连缀成一趟包罗万象、线索纷繁的细密旅程。本文尝试细读二人延续至今的创作脉络,“解码” 绘画中的种种 “机关”,但愿以此丰富读者探入画中时空的境遇体验。

“材料和媒介就是地气和身体的连结,它一定来自于外部世界给你的知觉。” 对从小就迷恋地理的史怡然来说,“大部分地理名词是形容词,岩层、植被、洋流、气旋,都拥有独特的景观、颜色、声音、气味,甚至本身就是隐喻。地理名词能标示并唤起很多感觉、记忆和想象。”

伴随多次或长或短的旅行和驻地,她把来自五湖四海的感觉、记忆和想象诉诸画中的色彩、对象与空间,好像要把观者传送到令她兴奋不已却又隐隐作祟的匿名目的地。赫尔曼 · 麦尔维尔在其名著《白鲸》的开篇详细描述了挂在大鲸客店过道护壁板上的一幅已经被烟熏得模糊不清的大油画:“在这幅画的中央,有一种叫不出名来的泡沫,上面依稀浮着三根蓝色的直线,直线上面高悬着一团又长又软又怪又黑的东西。真是一幅泥泞、潮湿、黏糊糊的画,神经过敏的人看了准会心烦意乱。然而,它却透露出一种无限的、半已把捉到的、难以想象的崇高性,在它跟前一站真有点挪不开步,逼得你不由自主地立下誓来,非把这幅怪画弄个明白不可。不时有一个突如其来却可惜靠不住的想法掠过心头。——那是午夜狂风大作的黑海,那是地、水、火、风四大自然力之间的一场狠斗,那是一丛枯萎了的石南,那是北国的冬景,那是冰封的时间之流解冻了。可是这些猜想最终都在画中央那团怪东西跟前站不住脚。一旦把那东西弄明白了,其他的就都会迎刃而解。不过,且慢;那东西不是有点像条大鱼,甚至就是大海兽吗?其实,作者的构思似乎是这样的——这是我个人最终的推测,我跟一些上了岁数的人就此画交谈过,因而也部分地综合了他们的意见。这幅画画的是强飓风中一艘合恩角船;这艘业已半沉只剩下三根光秃秃的桅杆在外面的船还在那里挣扎;一条激怒的大鲸打算整个儿跃过这艘船,只怕会戳穿在这三根桅杆上。”

吸引 “我” 的画中谜团几乎成了整本书的预告;而时隔一个多世纪后,村上春树把小说《舞!舞!舞!》中的一个关键地点命名为 “海豚宾馆”,以此致敬“大鲸”。史怡然的首个系列创作也叫“海豚宾馆”,两本小说带给读者的刺激的冒险感在其画中同样如影随形。或透明潜伏、或横冲直撞的海豚与各种没有五官的人物遭遇在斑驳剥落的场景,多层视界的皮层在画中交叠、平行乃至倒错。科幻感的色块、光线与图案暗示着多起神秘事件正在激烈地同时发生。悬疑惊悚的气氛继续弥漫在后续的“孔雀镇” 与“失物招领”系列中:没有五官的人的头部,沾染着血色的一块不规则形布料漂浮在空中,跃起的海豚形象再次出现;只是画面不再那么繁忙,事件悬而未决,如 Glitch 突然断裂或破碎的区块以史怡然自称为 “色轮” 和“光谱”的形式更明显地从画中辨识出来,并延续到后来的 “Mirage” 系列中。她曾不止一次谈到对讲究色彩关系和谐这一传统的反叛,浓郁的、反差的色彩在画中肆无忌惮地碰撞,而 “色轮” 和“光谱”的色彩形式增强了颜色独立于造型的发声。色彩独立的另一位 “得力助手” 是硬边效果的营造,其制作起初运用胶带;而在 2024 年的新作中,艺术家已经可以在木板上用画笔画出类似胶带的效果。

这种效果造就了画中清晰、甚至锋利的边缘和轮廓线,另一方面,与之配合无缝的是史怡然一向喜用的大笔刷,一笔就是一笔,毫不含糊。在《敖鲁古雅之窗》(2024)的右侧,百叶窗外木屋的墙面是一笔大刷子棕色的垂直线条,中间横向被一条浅灰色的百叶窗棱利落地切开。盖在木屋上的雪顶像粗粝的混凝土肌理,垂在房檐的部分似乎是染上了夕阳的红霞,毛毛剌剌地裹着樱粉色。在同一幅画中更大的面积里,颜色同样扮演着彻底切隔画面的纯粹区块,画面上方呈圆弧形层层如洋葱般扩散的多个 “太阳光晕” 的外沿几乎相切、平行或倒转(类似的色轮已多次出现在其画作中,例如《车站》(2016)和《艾略特的书房》(2022)),黄昏的鸡尾酒从耀眼的明黄到醉人的嫣红便如此调制成同一平面上的分层味道。若看得再久一些,微醺的眼会分不清窗之内外,日夜交接的魔幻时刻融化在这片寒冷的窗台,被艺术家还原成梅红、草绿、深紫和靛蓝,分别装入透明塑料罐和疑似颜料管的容器中。茄紫色罐盖下甜腻的梅红夕阳浆液是缩小版的多个 “太阳光晕” 轮,它们挤在罐子里,仿佛在打开的一刹那就会爆炸。而承托着三个 “颜料管” 的暗灰色在画面左下方形成一种基座,提醒着观者旋即到来的黑夜。

工作室画廊创始人庄彬曾生动地指出史怡然在《捕梦网》(2023)中对在地性色彩的把握带给他的美国艳阳:“别人到了美国是调时差,她调的是’色彩差’。”

在此次展出的其他画作中,色彩并不总是如此跳脱,色轮与光谱的衔接也显得更为丝滑流畅。早先画作中强烈的区隔与并置,在新近的画作中则融合为更可信的整体感;同时保留了多重视角与多来源的对象,两者相辅相成地共同营造出画面多层次的空间感。史怡然曾谈到自己的绘画要在西方逻辑、几何的透视系统之外,去还原人自然地感知环境的方式。“以前我们在学画的时候,老师让我们看准一个型,要眯起一只眼睛。这本身就是违反视觉机制的…… 人有两只眼睛,我们眼珠是会转的。…… 其实更古早一点用艺术去解释世界的方法,像是各种传说或者史诗,才是真正我们跟世界交往的一种方式。…… 不停地根据不同的碎片和侧面去拼凑。没有人能看到全貌,因为我们置身其中,被包裹在里面。”

将这种感知方式实现到画面上依赖大量技巧与经验的累积。例如为了营造层次,史怡然一般会先刷底,而后,单个色域的内部是一遍完成的。在从三维转化为二维的过程中,相近的颜色连在了同一个平面上。她说,就像爱德华 · 马奈的《阳台》(1868-1869),画面中间男子的黑衣服与整幅画的暗黑背景连在一起;但从轮廓来说,又是他与左右两位女子、共三个人的轮廓。马奈这幅著名的描绘现代巴黎的转型之作在构图上其实还借鉴了弗朗西斯科 · 戈雅比他早差不多半个世纪的《阳台上的少女》(1808-1814):阳台的护栏与画面本身的平面重叠;这与前面提到的色域和轮廓相配合,共同增强了马奈开创性的平面化效果。

史怡然将画家的视觉经验库形象地称作时常可被调取出的 “典故”,其中既包含真实生活经验中积累的视觉记忆以及相关的影像或手稿存档,也不乏丰饶艺术史上的先辈实践还有影视作品,而两者会在其作为一名画家的感知与思考中自动地相互交织。“画家离不开视觉经验。好比一个小说家永远是在跟文字打交道;而艺术家在看一个东西的时候,都会受到艺术史的影响。在学习的过程中,其实很难离开这些强大的艺术史的视觉传统。我在旅行的当下会去抓取到一些片段,回来以后其实会不自觉地把它们进行分类。” 借鉴与致敬是艺术创作的常见做法,杰夫 · 沃尔模仿过的经典名画、电影场景与广告镜头中就包括马奈的绘画。这些艺术史上的视觉被沃尔称作 “艺术的病菌,但在这里却转化成一种兵器。” 这些典故之于不同艺术家的给养不尽相同,然而一般来说,一名杰出的画家首先也是杰出的鉴赏家。史怡然往往会因艺术家具备系统化的、自足的视觉语言而被由衷地吸引。安德鲁 · 怀斯画的旷野中一栋建筑的窗户同时连接着室内的孤寂与户外的荒蛮,弥散出难以接近的神秘感;马提亚斯 · 怀瑟画中多层次空间感的混乱与和谐;爱德华 · 霍珀高对比的、有时过于饱和的、孤独的光线…… 都是她曾反复琢磨的 “典故”。

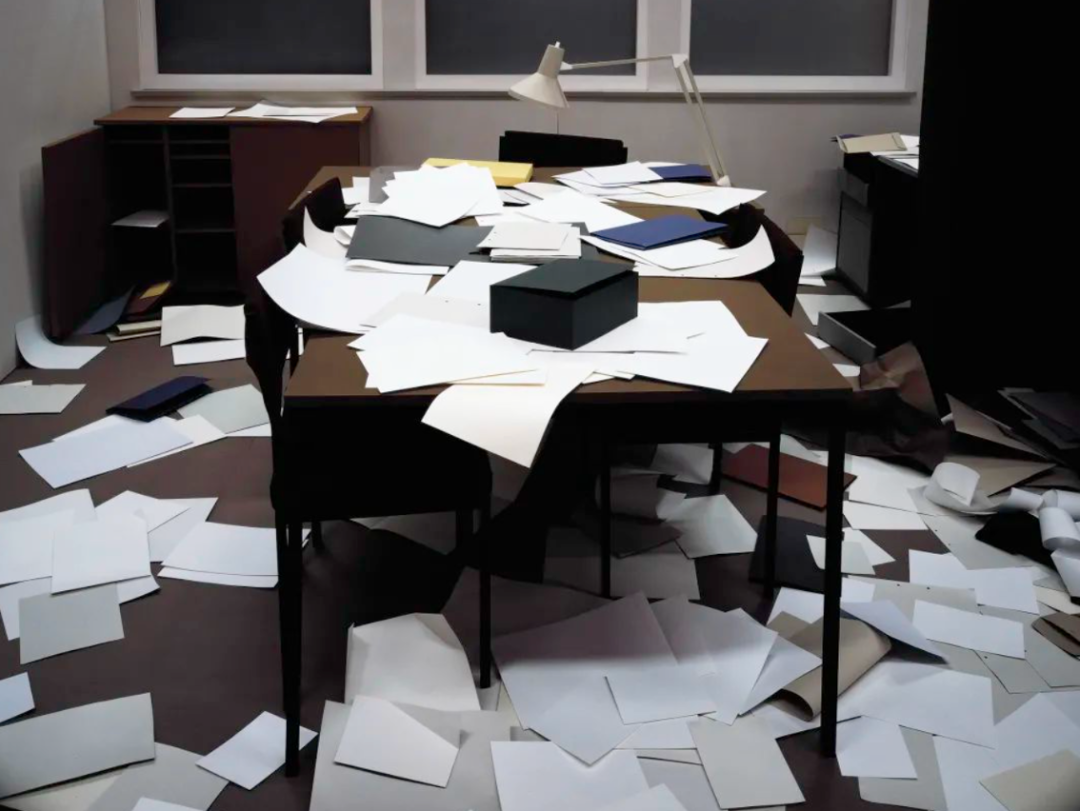

还有一位艺术家的创作表现出对历史的独特理解:托马斯 · 迪曼德重塑的历史图像之一《办公室》(Office,1995)中从当下重访历史的距离感与日常感曾激发史怡然以图像表现纸张的创作冲动。这一连接显得十分微妙,重大历史时刻现场的材料的质感细节对两位艺术家构成了相似的吸引力。施瀚涛在谈到迪曼德于历史图像的基础上建模以后重新拍摄的照片时曾说,“关于一个历史场景,或者是参与到一个历史场景里面去、今天的人参与到过去的某一个地点。其实地点有时候就是时刻,在这里时和空是相通的。”

他精妙的感悟让我联想到提出 “历史时间是多层的、以不同速度流逝的” 这一颠覆性观点的历史年鉴学派。在其领军人物费尔南 · 布罗代尔的历史眼光下,与结构和长时段相对应的时间被称为 “地理时间”。他曾说:“多少世纪以来,人类一直是气候、植物、动物种群、农作物,以及整个慢慢建立起来的生态平衡的囚徒。” 同样在长时段制约着人类社会的其它要素还包括思想构架的限制,而思想构架也难逃环境的影响。回到史怡然长久以来缘自感知与地理之间关系的创作热情,以及她对人文地理的历史演化的关注,她画中对 “此地彼时” 距离感的把握以亲历者或代入者的人称展开,由此包含的鲜活的身体经验联同她摘取自视觉与阅读的 “典故” 构成了其绘画的真正素材库。“直到今天,我工作的重心仍然是通过观看来形成一个有距离的叙述。但这种叙述又与摄影或传统的写实绘画不同——它是一种更为内在的叙述,是我在通过双眼实践我的视觉理论,我看到的事物转变成了我,或者说我的精神只能通过双眼走出来,于是我自身亲历了这个系统再从中钻出来,然后把其中所见按自己感知的次序叠加呈现,这就是我的绘画对现实的转化,它还是它但又不再是它。这种转化绝不是靠外在的逻辑来推测和演绎,我只用在地的语言,也就是我看到的形与色——只是这时的形与色经过我的身体已经揉碎并重组,从某种意义上来说已经是抽象的,但它们可以透过视觉得到还原,从而形成一种我这个亲历者自己的描述。”

绘画是一种特定的输出。就像史怡然在上面这段自述中尝试说明的那样,而她在着手绘画前一直会自问 “有没有必要把它画出来?如果用影像、照片等其他媒介能把想要表达的事情讲得更清楚,那是否就不需要去把它画出来了?” 她也曾态度鲜明地表达过,“绘画是否已死”是个伪命题,她觉得今天 “绘画反而活得更好了…… 具象绘画提炼的景象是一种质地,而不再是叙事或者单纯的事件了”。持同样观点的艺术家不乏其人,韩梦云曾从非殖民化的视角反驳过这一“狭隘” 的讨论,吕克 · 图伊曼斯也直言不讳地向绘画“表白”:“我他妈的才没有那么幼稚。绘画是人类已知的第一种概念性图像,绘画就是艺术。你用双手作画,你有无尽可以把玩的细节。…… 一张画是有非常多层次的,它的指向也可以是非常多元的。绘画是有强烈触感的,它有温度,它用物质性的颜料来创作,画在画布上,它会让你看出许多不同。绘画就是独特的。”

而且一位对绘画 “忠诚” 的艺术家永远不可能满足已有的“功夫”,史怡然说她近期痴迷于画各种特征鲜明的质感和触感,比如毛皮。她每次只画一幅画,面对每一幅画,她都想继续拓展语言的表现力。这种企图心抑或说挑战并非总能达成,史怡然曾如此比较游泳与绘画:“喜欢游泳是因为它与画画完全相反。随着练习的累积,可以非常清楚地感受到技术上的提高,无论速度还是耐力,这种进步毫不含糊。那种不断形成的永久性的身体记忆不会辜负你。而在画画中很难得到这种付出与回报对等的成就感,反而经常是画了几天的画因为一笔就毁了,又回到原点。那种挫败感只有在游泳的时候能得到弥补。”

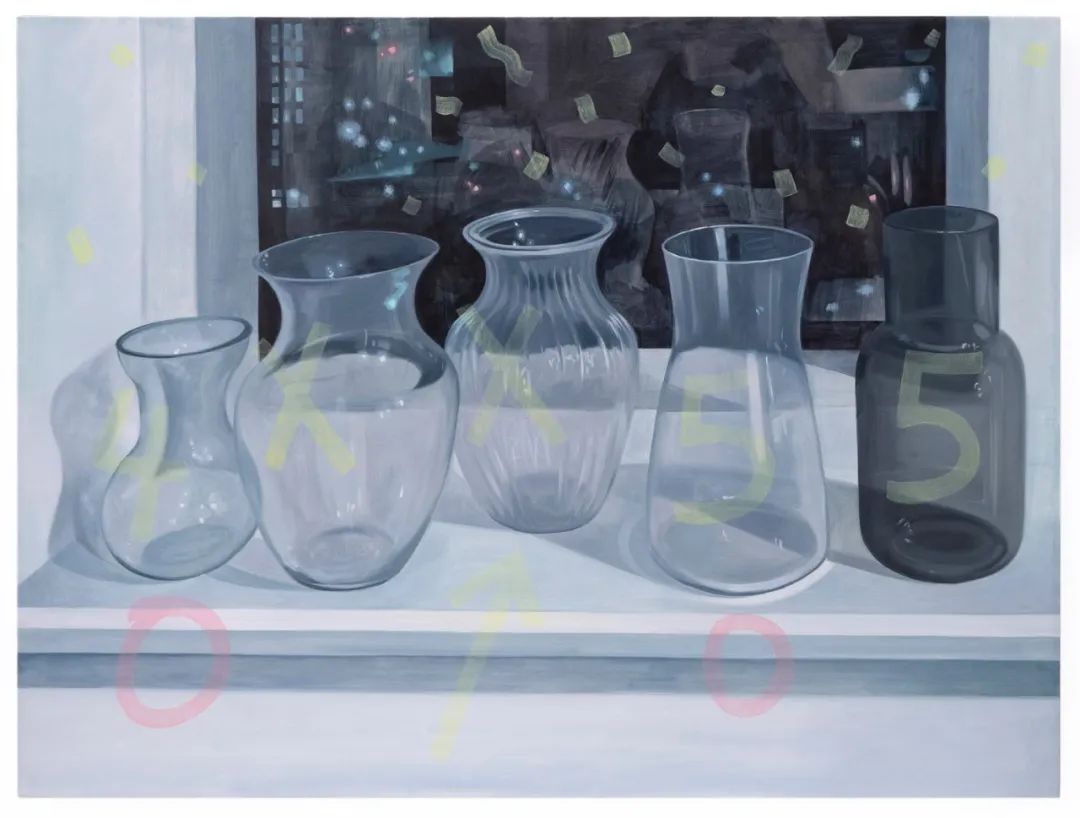

多重视角以半透明的复数图层贯穿于黄宝莹的具象绘画,玻璃窗以及其他玻璃器皿成为她常用的画面介质与对象。玻璃窗内与外的场景透过画布与窗户并置且略有重叠,前景中视线出发点的明亮对应着镜面另一侧的晦暗,清晰对应模糊,占据画面中心的静物对应更纷繁的室内或室外场景。此外,有时她还会叠加上如水印般的透底图层,可能是花与叶(如《乐园》(2024))、数字(如《漫长的告别》(2024))、星辰(如《属于宇宙的承包商之一》(2023))或铁链(如《妈妈》(2022))。这些意象往往来源于她绘画同期的日常生活经历,以及她从观影和阅读中获得的意象及感想。

在一个黄宝莹典型的画面中,夜晚的窗前,室内开着灯,独自一人的目光,对着玻璃窗望向窗外。窗外楼宇星星点点的窗户与灯光,是典型的都市夜晚的住宅区。不同于闹市的灯火通明,这些楼宇和街道的大多数面积都藏在暗部。而居住其中的家家户户是密集的,可望却不可及,陌生,隔离。画内拂动着风与气息,以及目光主人的一点点孤独和坚持。

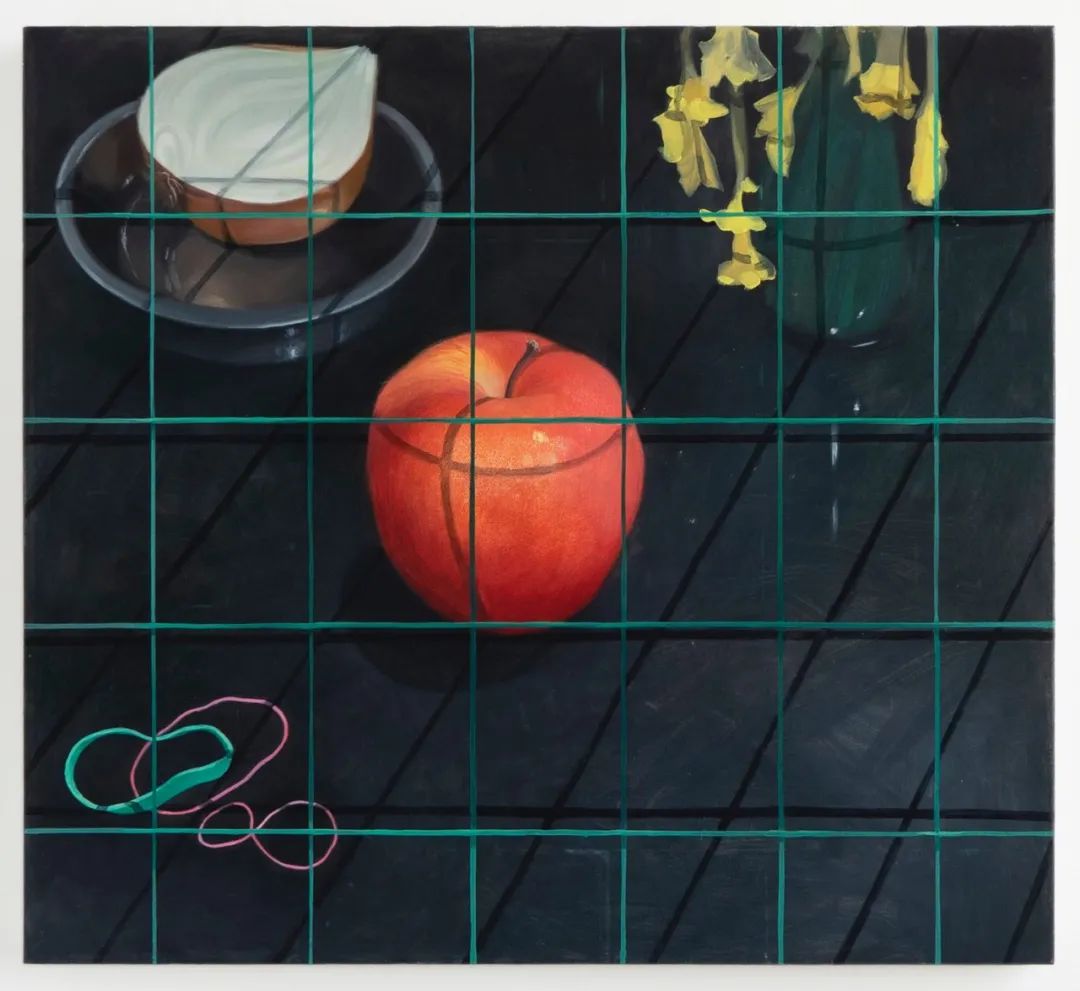

这种坚持有时会表现为激烈的抗议姿态,因为黄宝莹并不避讳选用一些非常直接甚至暴力暗示的形象:除了刚才提到的铁链,还有绳索吊圈(《未知的荆棘之一》,2023)与绿色隔离网(《禁忌家园》,2022)。而时常作为画面主题出现的盆栽与切花共享着被限制的生命形态,不论花朵盛开抑或凋零(《不要软埋》(2023)),又或是姿态舒展但显得乖顺的绿植,对其生命延展的限制都赫然在场。

透过图像接近的日常总是那么有魅惑力,比现实更活色生香。即便乍一看平淡无奇,但倾注情感的绘画本身自会化平淡为神奇。如《工作室观察》(2021),斜倚在墙边的一张空白画布,似乎在安静地等待;插在一旁插座里的黑色电线轻轻围绕起画布的一角,延伸到另一头的吹风机。吹风机的口靠在一个木色的小搁板上,冲着画布,就好像是在回应面前这片空白的无声的期待。

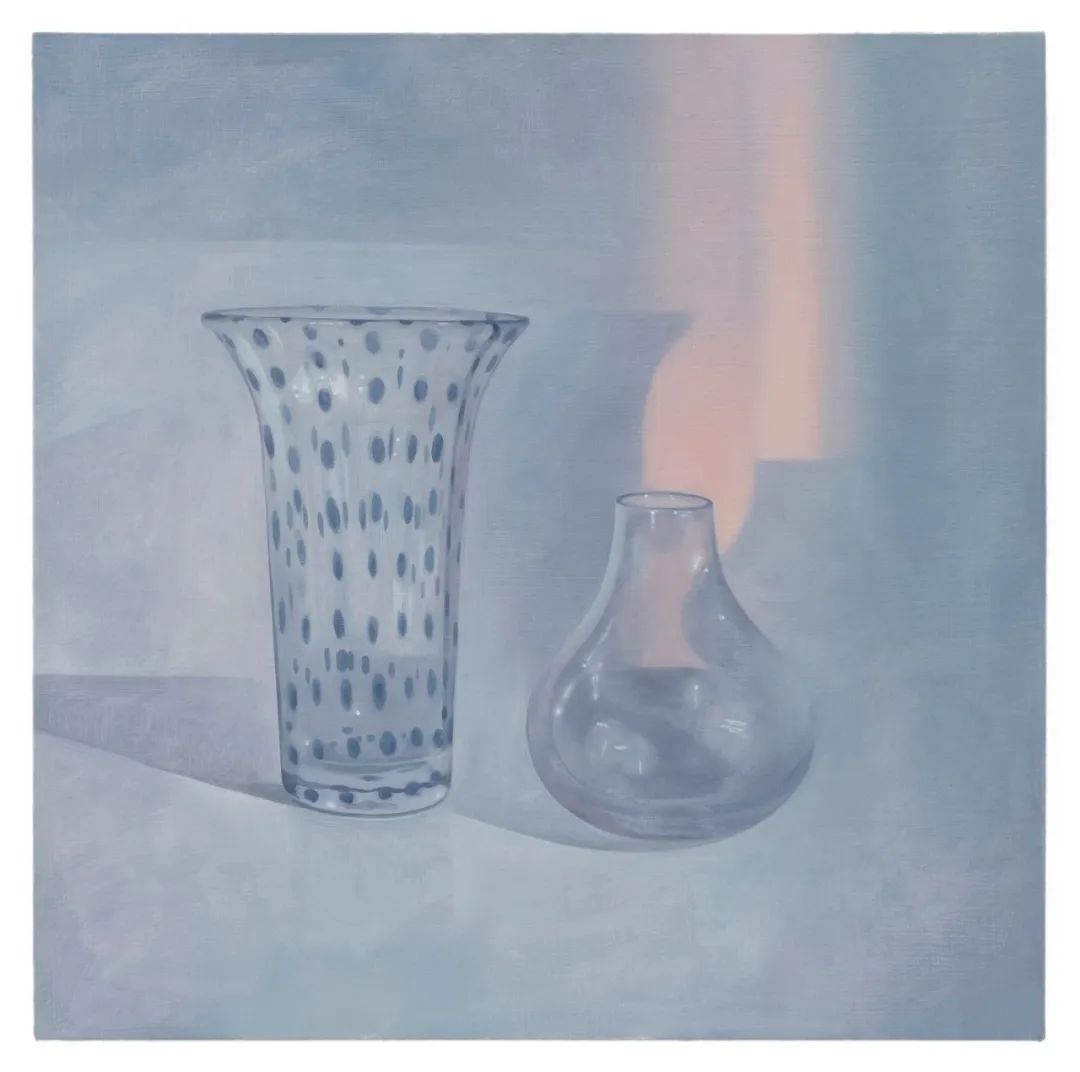

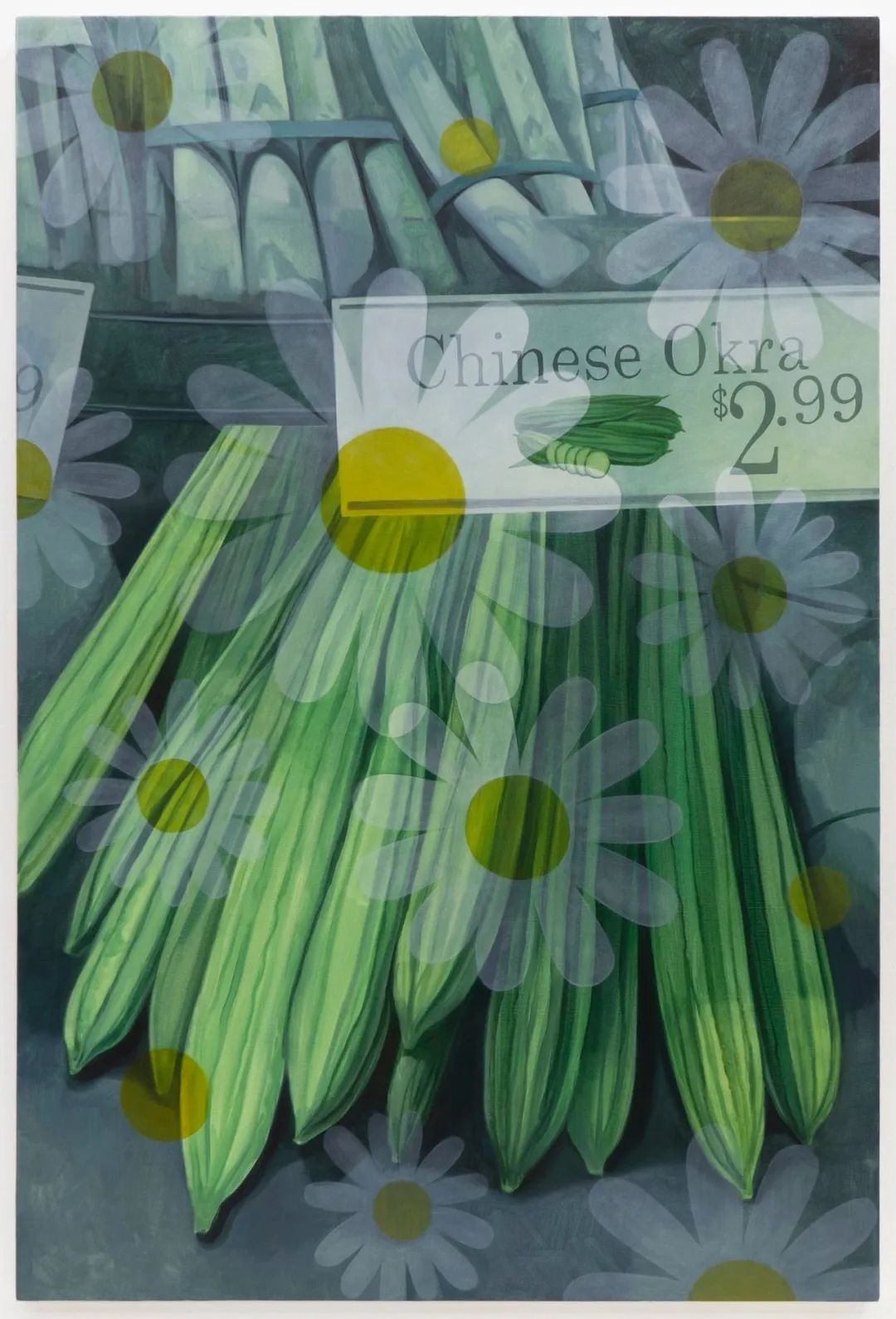

半透明的玻璃器皿,如形形色色的玻璃杯与瓶瓶罐罐,在其细致入微的描绘中好像成了日常这部戏剧中的不同角色。《闪光的日子》(2022)的晶莹剔透与协同感,《毕业清仓》(2023)里一字排开的社群感,《早秋的傍晚》(2024)的氤氲淡彩…… 作为经典的静物画的题材,这些器皿的半透明、中空与反光等质感的重现,浸润着绘画者细腻无间的关切目光与手部动作。对于半透明质感的把握也延伸到透底图层的方法,例如《美国黄瓜》(2023)中丝瓜、小雏菊与货架标识 “Chinese Okra”(中国秋葵)半透明地交叠,而黄瓜、丝瓜与秋葵的互文轻巧地暗示着身份差异。

黄宝莹的坦培拉绘画也在展览中首次亮相,这种可追溯至中世纪的古老材料以柔和的、自带温度的色彩和触感,明显地区别于油画和丙烯。坦培拉三联画《用三种方法观察浴缸底部》(2024)都基于同一张照片。对黄宝莹来说,面对摄影参考图的观察可以突破写生时肉眼的很多边界,由此在对画面的重复观看与多视角的重复描绘中拓展体验。

这让我联想到与之 “对称” 的多联幅实践,比如杰夫 · 沃尔曾用三联幅来展示 “一张” 照片:《楼梯与两个房间》(2014)。左幅画面中,一名男子从一扇虚掩的门后探出头来,闭着眼睛像是要听到什么;中幅画面里,左幅中的那扇门关着,门外的楼梯与走道占据了大部分画面;右幅呈现了一个左右对称的室内空间,墙角左右各有一扇门,左墙挂着一幅画框,右墙前的一张床上躺着一名穿着睡袍的深肤色男子,他单手撑着头直视向画面外。同一个摄影镜头不可能同时出现在这三幅画面的空间,然而沃尔有意赋予画面的连贯性让这三幅画面并置于同一视界,由此为观者打开了一种超越实体观看规律的可能。

在此次展出的另一组双联画《漫长的告别》(2024)中,两个视角的来回转换夹带着艺术家在最近一次搬家时对旧家的不舍与对新家的期待;这次搬家是她在过去留学九年的多次搬家中与众不同的一次,因为它终于意味着相对稳定与松弛的状态。或许在新家给予的新一阶段的安稳感中,黄宝莹画里的日常也将随之发生超越以往流离感的变化。

The relationship between place and time is always winding and complex.

Although the works in this exhibition primarily feature indoor still lifes and home scenes by Huang Baoying and locations from her travels where Shi Yiran stayed or visited, the driving force behind both artists’ work stems from their intimate connection with the idea of home and migration. For Huang, who has lived abroad for years, from Shenzhen to New York, “home” has always been temporary and unstable. The frequent moves and the insecurity of fluctuating between the identities of host and guest have recently shifted toward a more stable and relaxed state with her latest move. For Shi, from Inner Mongolia to Hangzhou, time has not dulled her sense of rootlessness in a foreign place; instead, it has sparked a strong interest in her homeland. She has become particularly fascinated with understanding the long history of these places, which led her to conduct cultural and geographical explorations in Hulunbuir and the Greater Khingan Range.

Both artists’ paintings are realistic and figurative but not necessarily aimed at reproducing reality. Even though viewers can easily recognize the potted plants, floral arrangements, fireworks, curtains, lamps, dolls, maps, and museum display cases depicted in the paintings, in the works, they appear as observations of phenomena flowing through time: seemingly quiet, yet with hidden undercurrents. Andrei Tarkovsky wrote in his film diarySculpting in Time, “It is still in one moment, but it is also permeated with the continuous flow of time, carrying abundant emotions and thoughts… Time is a condition, a flame, in which the fire of the human soul resides…… Time and memory blend like two sides of the same coin.” Therefore, the present moment is almost unattainable, and any attempt to capture it can only freeze it in the past; only through distance and separation can one revisit the past moment. The works in this exhibition create space through this distance and separation; furthermore, the paintings become places. These places can exist independently or together as vivid interpretations of traveling or staying in time.

Their past paintings have already showcased the diversity of time and space, used collage and overlapping techniques to juxtapose images from various sources within a single frame. Much like Richard McGuire’s groundbreaking graphic novelHere, which depicts a house in New Jersey over millions of years, presenting the passage of time in a multi-paneled format on each page, creating a detailed journey rich with diverse threads. This article closely reads the two artists’ creative paths, aiming to “decode” the various “mechanisms” within their paintings and enrich the reader’s experience as they delve into the time-space depicted in the artworks.

“Material and medium are the connections between the earth and the body, undoubtedly stemming from the perceptions the external world gives you.” Shi Yiran, fascinated with geography since childhood, says, “Most geographical terms—strata, vegetation, ocean currents, cyclones—all possess unique landscapes, colors, sounds, and smells, and they can even be metaphors in themselves. Geographical terms can mark and evoke many sensations, memories, and imaginations.”

With each of her various travels and residencies, whether long or short, she channels the feelings, memories, and imaginations from all over the world into the colors, objects, and spaces in her paintings, as if attempting to transport the viewer to an anonymous destination that excites her yet also subtly haunts her. In the opening of Herman Melville’s classicMoby-Dick, he vividly describes a large, smoke-blurred painting hanging in the corridor of the Spouter-Inn: “But what most puzzled and confounded you was a long, limber, portentous, black mass of something hovering in the centre of the picture over three blue, dim, perpendicular lines floating in a nameless yeast. A boggy, soggy, squitchy picture truly, enough to drive a nervous man distracted. Yet was there a sort of indefinite, half-attained, unimaginable sublimity about it that fairly froze you to it, till you involuntarily took an oath with yourself to find out what that marvellous painting meant. Ever and anon a bright, but, alas! deceptive idea would dart you through.—It’s the Black Sea in a midnight gale.—It’s the unnatural combat of the four primal elements. —It’s a blasted heath. —It’s a Hyperborean winter scene. —It’s the breaking-up of the ice-bound stream of Time. But at last all these fancies yielded to that one portentous something in the picture’s midst. That once found out, and all the rest were plain. But stop; does it not bear a faint resemblance to a gigantic fish? even the great leviathan himself?

In fact, the artist’s design seemed this: a final theory of my own, partly based upon the aggregated opinions of many aged persons with whom I conversed upon the subject. The picture represents a Cape-Horner in a great hurricane; the half-foundered ship weltering there with its three dismantled masts alone visible; and an exasperated whale, purposing to spring clean over the craft, is in the enormous act of impaling himself upon the three mast-heads.”

The mystery that captivated “me” in the mystic painting almost became a preview for the entire book; more than a century later, Haruki Murakami paid homage toMoby-Dick by naming a key location in his novel Dance Dance Dance “Dolphin Hotel.” Shi’s first series of works was also titled “Dolphin Hotel,” the thrilling sense of adventure that the two novels brought readers is similarly ever-present in her paintings. Dolphins, transparently lurking or charging headlong, encounter faceless figures in weathered, peeling scenes where layered perspectives overlap, parallel, or even invert. Sci-fi-inspired blocks of color, light, and patterns hint at multiple mysterious events happening intensely and simultaneously. The suspenseful and eerie atmosphere continues in her subsequent series “Peacock Town” and “Lost and Found”: faceless heads, an irregular blood-stained piece of fabric floating in the air, and the reappearance of the leaping dolphin image. However, the scenes are no longer as busy, the events unresolved, with glitch-like blocks suddenly fractured or broken, more clearly recognizable in the form of what Shi calls “color wheels” and “spectrums,” which extend into her later “Mirage” series. She has mentioned more than once her rebellion against the tradition of harmonious color relationships, with bold, contrasting colors colliding recklessly in her paintings. The color forms of “color wheels” and “spectrums” amplify the independent voice of color, separate from form. Another “helping hand” in the independence of color is the creation of hard-edge effects, initially made using tape; in her new works from 2024, the artist can now achieve similar effects with a brush on wood panels.

This effect creates sharp, even razor-like edges and contour lines in the paintings, seamlessly complemented by Shi Yiran’s consistent use of large brushes, where one stroke is a decisive, unambiguous statement. On the right part of the Window of Olguya Evenk Ethnic Township (2024), Shi paints the wall of a wooden cabin outside the blinds with vertical brown strokes using a large brush, neatly intersected horizontally by the light gray slat of the blinds. The snow on the cabin roof resembles the rough concrete texture, with the part hanging over the eaves rendered with the pink of the sunset, rough-edged and wrapped in cherry blossom hues. In a larger area of the same painting, color similarly plays the role of entirely dividing the composition into pure blocks. The upper part of the painting features multiple layers of “sun halos,” expanding in an onion-like arc, almost touching, paralleling, or inverting each other (similar color wheels have appeared in her works multiple times, such as in The Station (2016) and The Study of Eliot (2022) ). The twilight cocktail mixes from brilliant yellow to intoxicating crimson, creating layered flavors on the same plane. Suppose you look a little longer; your slightly dizzy eyes might blur the distinction between inside and outside the window. In that case, the magical moment of day meeting night melts on this cold windowsill, which the artist translates into plum red, grass green, deep purple, and indigo, placed into transparent plastic jars and containers resembling paint tubes. The sweet, sticky plum-red sunset syrup under the eggplant-colored jar lid is a miniature version of multiple “sun halos” squeezed inside as if they might explode when opening the jar. Supporting the three “paint tubes,” a dark gray color in the lower left forms a base, reminding the viewer of the imminent arrival of night.

Studio Gallery founder Zhuang Bin vividly pointed out how Shi Yiran’s grasp of local colors in Dreamcatcher (2023) brought him the American sunshine: “Others adjust to the time difference when they arrive in America, but she adjusts to the ‘color difference.’”

In the other works exhibited this time, the colors are sometimes bold, and the transitions between color wheels and spectrums appear smoother and more fluid. Shi’s earlier works’ strong contrasts and juxtapositions have blended into a more cohesive overall sense in her recent paintings. While retaining multiple perspectives and multi-sourced objects, these elements combine to create a richly layered sense of space in the compositions. Shi has mentioned that her painting aims to restore the natural way humans perceive the environment outside of the Western logic and geometric perspective system. “When I studied painting, my teacher would ask me to focus on a shape and squint one eye. This method goes against the visual mechanism. Humans have two eyes, and our eyeballs move. In fact, the earlier methods of using art to explain the world, like various legends or epics, were the real ways we interacted with the world… Constantly piecing together different fragments and sides. No one can see the whole picture because we are all inside it.”

Realizing this way of perception on canvas requires a significant accumulation of technique and experience. For instance, Shi usually starts with an undercoat to create layers, then completes each color area in one go. Similar colors come near each other on the same plane, translating from three dimensions to two. She explained that it’s identical to how Édouard Manet’sThe Balcony (1868-1869) connects the black clothes of the man in the center with the dark background of the entire painting; yet, in terms of contour, it’s the outline of him together with the two women on either side, forming three distinct figures. Manet’s famous work, depicting the transformation of modern Paris, draws on Majas on a Balcony (1808-1814) by Francisco Goya, created nearly half a century earlier: the balcony railing overlaps with the flat plane of the painting itself. Thus, Manet strengthened his groundbreaking flattening effect.

Shi vividly refers to a painter’s visual experience repository as useful “allusions.” This repository includes visual memories accumulated from real-life experiences, related images or manuscript archives, and the rich practices of predecessors in art history and film works. These elements automatically intertwine within her perception and thinking as a painter. “A painter cannot escape visual experience. It’s like a novelist who is always dealing with words; an artist, when looking at something, is inevitably influenced by art history. During the learning process, it’s actually very difficult to detach from these powerful visual traditions of art history. When I’m traveling, I capture certain fragments, and after returning, I unconsciously categorize them.” Borrowing and paying homage are standard practices in artistic creation. Jeff Wall, for instance, has mimicked classic paintings, movie scenes, and advertising shots, including works by Manet. Wall referred to these art historical visuals as “the germs of art, but here they are transformed into weapons.” These allusions nourish different artists in different ways, but generally, a great painter is, first and foremost, a great connoisseur. She is genuinely attracted to artists who possess a systematic, self-sufficient visual language. For example, Andrew Wyeth’s depiction of a building’s window in the wilderness connects the solitude of the interior with the wildness of the outdoors, emitting an elusive sense of mystery; Matthias Weischer’s chaotic yet harmonious multilayered spatial sense in his paintings; Edward Hopper’s high-contrast, sometimes overly saturated, solitary light—all are “allusions” she has pondered over repeatedly.

Another artist whose work reflects a unique understanding of history is Thomas Demand. One of his reconstructed historical images,Office (1995), with its sense of distance and everydayness in revisiting history from the present, once inspired Shi to explore the portrayal of paper through images. This connection is quite subtle, as the textural details of materials from significant historical moments hold a similar attraction for both artists. When discussing Demand’s photos, which he reshot after modeled them based on historical images, Shanghai-based art critic Shi Hantao once remarked, “Regarding a historical scene, or participating in a historical scene, where people today engage with a past location—sometimes the location is the moment itself. Here, time and space are interconnected.”

His profound insight reminds me of the Annales School of History, which introduced the groundbreaking idea that “historical time is multilayered and flows at different speeds.” Under the historical perspective of Fernand Braudel, a leading figure of this school, time corresponding to structures and the long duration is called “geographical time.” He once said, “Man has been prisoner for entire centuries of climates, vegetation, animal populations, cultures; in other words, a slowly constructed equilibrium that one cannot challenge without threatening everything.”

Other factors constraining human society over the long term include the limitations of environmental-born mental frameworks. Returning to Shi’s long-standing passion for the relationship between perception and geography in her work, as well as her focus on the historical evolution of human geography, her grasp of the sense of distance between “here and then” is expressed from the perspective of a participant or an involved observer. The vivid bodily experiences contained within, combined with the “allusions” she draws from visual and literary sources, constitute the actual material of her painting. “To this day, the focus of my work is still to form a narrative with distance through observation. However, this narrative differs from photography or traditional realistic painting in that it is a more internal narrative. I am practicing my visual theory through my eyes. What I see transforms into me, or rather, my spirit can only emerge through my eyes. Thus, I experience this system firsthand, then reemerge from it, layering what I see in the order of my perception. This is how my painting translates reality; it is still itself, but also not itself. This transformation is never speculated or interpreted through external logic. I only use the local language- that is, the shapes and colors I see—but at this point, my body has fragmented and reorganized the shapes and colors. In a sense, they are already abstract, but they can be restored through vision, thereby forming a description unique to me as the participant.”

Painting is a specific form of output. As Shi tries to explain in the above statement, she always asks herself before starting a painting, “Is it necessary to paint this? If using video, photography, or other media can express what I want to say more clearly, then is there still a need to paint it?” She also thought that “Is painting dead?” was false. She believes that today, “painting is alive… The scenes refined by figurative painting are a texture, no longer a narrative or just an event.” Many artists share this view. Artist Han Mengyun has refuted this “narrow” discussion from a decolonization perspective, and Luc Tuymans has bluntly expressed his “love” for painting: “I’m damn sure I’m not that naive. Painting is the first conceptual image known to humanity, and painting is art. You paint with your hands; there are endless details you can play with. A painting has many layers, and its directions can be very diverse. Painting has a strong tactile quality and warmth; it is created with canvas material paint, allowing you to see many different things. Painting is unique.”

Moreover, an artist “loyal” to painting can never be satisfied with their existing “skills.” Shi Yiran says she has recently been obsessed with painting various distinct textures and tactile sensations, such as fur. She only paints one painting at a time, and with each one, she wants to continue expanding the expressive power of the language. This ambition or challenge is only sometimes achievable. Shi once compared swimming to painting: “I like swimming because it’s the opposite of painting. With practice, you can feel the improvement in technique, whether in speed or endurance, and this progress is unmistakable. The permanent bodily memory built through exercises will never let you down. But in painting, it’s hard to achieve a sense of accomplishment that matches the effort and reward. Often, a painting you’ve worked on for days can be ruined by a single stroke, bringing you back to square one. That sense of frustration can only be compensated for when swimming.”

Multiple perspectives are woven into Huang Baoying’s figurative paintings through semi-transparent layers, with glass windows and other glass vessels frequently serving as mediums and subjects. The scenes within and outside of the glass are juxtaposed and slightly overlapped on the canvas, where the brightness of the foreground contrasts with the darkness on the opposite side of the glass, clear elements correspond with blurred ones, and still live at the center of the composition are matched by more intricate indoor or outdoor scenes. Additionally, she sometimes overlays watermark-like transparent layers, which could be flowers and leaves (as in Paradise, 2024), numbers (as in A Long Goodbye, 2024), stars (as in Contractor to the universe I, 2023), or chains (as in Moms, 2022). These images often originate from her everyday life experiences during the same period as her paintings and the imagery and ideas she gathers from films and reading.

In a typical scene by Huang, a solitary figure gazes through a glass window in the evenings with the interior lights on. The exterior reveals a residential area typical of an urban night, where nearby buildings’ scattered windows and lights are visible. Unlike the bright lights of a bustling city, most buildings and streets outside remain in darkness. Though the households within these buildings are dense, they are distant, unfamiliar, and isolated. Within the painting is a sense of wind and breath, accompanied by a hint of the figure’s solitude and quiet determination.

This determination sometimes manifests as a fierce, aggressive stance, as Huang does not shy away from using direct or violent imagery. Besides the chains mentioned above, she incorporates symbols like nooses (Unknown Thorns I, 2023) and green barriers (Forbidden Garden I & II, 2022). Potted plants and cut flowers, which frequently appear as central themes in her work, share a constrained existence. Whether the flowers are in full bloom or wilting (Don’t sink into oblivion, 2023), or the green plants are lush yet subdued, the limitations on their life force are strikingly evident.

The allure of approaching the everyday through images is always captivating, often more vivid and colorful than reality itself. Even when something might seem plain at first glance, a painting infused with emotion can transform the ordinary into something extraordinary. An example is Studio Looking (2021), where a blank canvas leans quietly against a wall as if waiting silently. A black power cord, plugged into a nearby socket, gently loops around one corner of the canvas, extending toward a hairdryer at the other end. The nozzle of the hairdryer rests on a small wooden shelf, pointed at the canvas as if responding to the silent anticipation of the blank space before it.

Through her meticulous depiction, translucent glass vessels, such as various glasses and jars, take on the role of different characters in everyday drama: the crystal clarity and sense of harmony in Glistening Days (2022), the communal feeling of the neatly lined-up items in Graduation Sale (2023), and the soft, diffused colors in Afternoon in early winter (2024). Huang recreates these vessels’ translucency, hollowness, and reflective qualities as a classic still-life subject with her delicate, intimate gaze and hand movements. Her mastery of translucent textures also extends to the use of semi-transparent layers, as in American Cucumber (2023), where loofahs, daisies, and the shelf label “Chinese Okra” overlap translucently, with the interplay of cucumbers, loofahs, and okra subtly hinting at differences in identity.

Huang Baoying’s tempera paintings are also making their debut in this exhibition. This ancient medium dates to the Middle Ages and is distinguished by its soft colors and tactile qualities that convey warmth, setting it apart from oil and acrylic paints. The tempera triptych To observe the bottom of the bathtub in three ways (2024) developed from a single photograph. For Huang Baoying, observing a photographic reference allows her to transcend many limitations of live observation, expanding the experience through repeated viewing of the image and multiple perspectives in the repeated depiction of the scene.

The triptych reminds me of the “symmetrical” multi-panel practice, such as Jeff Wall’s use of triptychs to display “one” photo: Stairs and Two Rooms (2014). In the left picture, a man sticks his head out from behind a half-open door, with his eyes closed as if he wants to hear something; in the middle picture, the door in the left picture is closed, and the stairs and corridor outside the door occupy most of the picture; the right picture presents a symmetrical indoor space, with a door on each corner, a picture frame hanging on the left wall, and a dark-skinned man in a nightgown lying on a bed in front of the right wall, supporting his head with one hand and looking straight out of the picture. The same camera lens cannot simultaneously appear in the space of these three pictures. Still, the wall intentionally gives the pictures a sense of coherence. It places these three pictures in the same field of vision, thus allowing viewers to transcend the rules of physical viewing.

In another diptych exhibited this time,A Long Goodbye (2024), the switching between two perspectives conveys the artist’s reluctance to leave her old home and her expectations for her new home during her most recent move; this move is unique among the many moves she has made during her nine years of studying abroad because it finally means a relatively stable and relaxed state. In the new sense of stability given by the new home, the daily life in Huang’s paintings will also undergo changes that transcend the previous understanding of displacement.

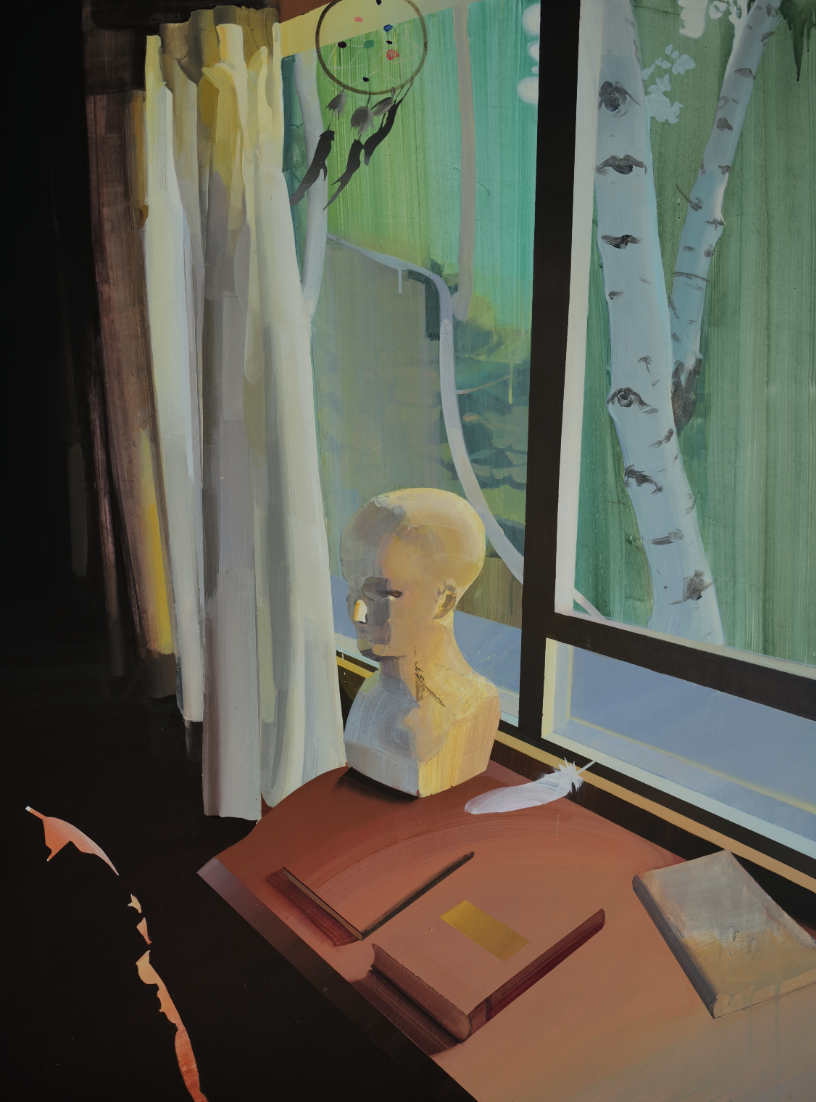

梦旅店 Dream Inn

木板丙烯 Acrylic on Wood Panel

120 × 90 cm

2024

©Shi Yiran. Courtesy Ferris Gallery

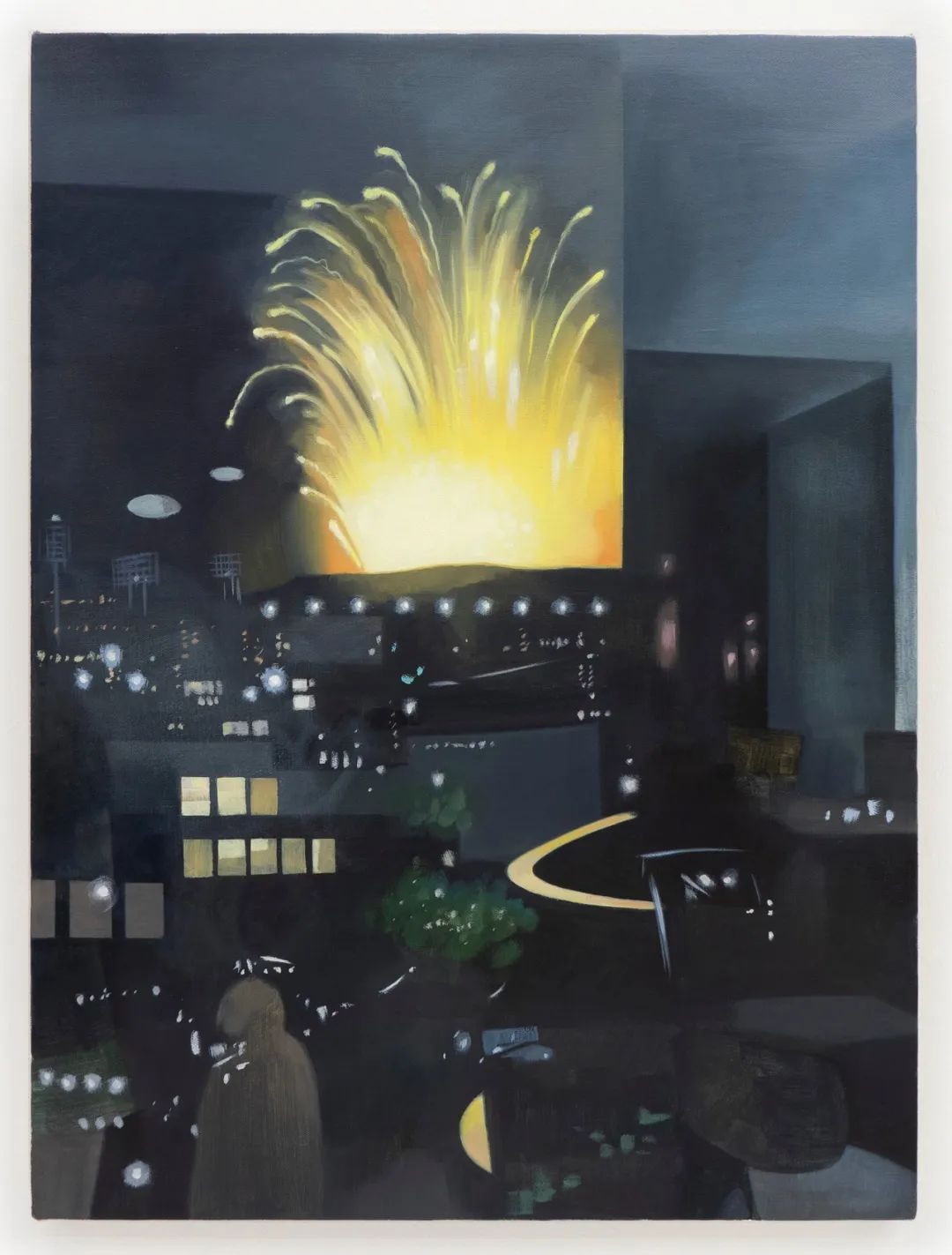

等到球赛结束 – 金色 Wait Until The Game Ends-Gold

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

61 × 45 cm

2022

©Huang Baoying. Courtesy Ferris Gallery

敖鲁古雅之窗 Window of Olguya Evenk Ethnic Township

木板丙烯 Acrylic on Wood Panel

80 × 100 cm

2024

©Shi Yiran. Courtesy Ferris Gallery

车站 Station

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

160 × 200 cm

2016

艾略特的书房 The Study of Eliot

肯特纸裱木板丙烯 Acrylic on Kent Paper on Board

71 × 87 cm

2022

爱德华 · 马奈 Edward Manet

阳台 The Balcony

170 × 124.5 cm

1868-1869

巴黎奥赛博物馆藏

The Collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris

(右 Right)

弗朗西斯科 · 戈雅 Franciso Goya

阳台上的少女 Majas on the balcony

194.8 × 125.7 cm

1810

纽约大都会艺术博物馆藏

The Collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

办公室 Office

彩色合剂冲印 Color negative film development

180 × 240 cm

1995

萨满博物馆 Shaman Museum

肯特纸裱木板丙烯 Acrylic on Kent Paper on Board

158 × 110 cm

2023

乐园 Paradise

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

203.2 × 152.4 cm

2024

属于宇宙的承包商之一 Contractor to the universe I

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

76.2 × 101.6 cm

2023

妈妈 Moms

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

122 × 9 1cm

2022

未知的荆棘之一 Unknown Thorns I

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

142 × 181 cm

2023

禁忌家园之一 Forbidden garden I

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

63.5 × 66 cm

2022

不要软埋 Don’t Sink Into O__blivion

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

152.5 × 116.8 cm

2023

工作室观察 Studio Looking

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

121.92 × 91.44 cm

2021

闪光的日子 Glistening Days

亚麻布油画 Oil on Linen

60.96 × 76.2 cm

2022

毕业清仓 Graduation Sale

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

60.96 × 60.96 cm

2024

早秋的傍晚 Afternoon in Early Winter

亚麻布油画 Oil on Linen

60.96 × 76.2cm

2022

美国黄瓜 American Cucumber

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

152.5 × 101.5 cm

2023

用三种方法观察浴缸底部 To observe the bottom of the bathtub in three ways

木板坦培拉 Tempera on Wood Panel

22 × 22 cm × 3

2024

©Huang Baoying. Courtesy Ferris Gallery

楼梯与两个房间 Staircase & Two Rooms

248.4 × 184.9 × 4.9 cm

2014

© Jeff Wall. Courtesy White Cube

漫长的告别 A Long Goodbye

布面油画 Oil on Canvas

76 × 76 cm × 2

2024

©Huang Baoying. Courtesy Ferris Gallery